FinTech Gamble: How Millennials Turned Wells Fargo's Rewards Card Strategy Into a $10 Million Monthly Drain

What you can learn from the strategic choices that went wrong

When fledgling FinTech startup Bilt was shopping around for a bank to partner with for its rent rewards card, incoming Wells Fargo CEO Charles Scharf’s stated top strategic goal was to expand their credit card business.

What better way than to partner with a hot startup?

More than anything else, Wells Fargo wanted to seem relevant and appear “hip” to capture more of a younger demographic.

It seemed like a perfect match.

Fast forward 20 months, and it’s becoming apparent that financially savvy young Millennials are using a few simple strategies to make the most of the card, costing Wells as much as $120 million a year.

And Wells Fargo is unfortunately coming across more like an inappropriately older person wearing trendy attire and speaking “cool” lingo in their attempt to appeal to young, affluent customers.

Behind the scenes

To understand why this is happening, we’ll dig into a few basics of how banks make money with credit cards and pull back the curtain on the co-branded rewards cards industry.

You most likely have a co-branded card in your wallet and may be paying rent now.

We’ll share how Wells gambled, the simple strategies that are beating them at their own game, and that you too can use to make rewards cards work for you.

Wells makes its first assumption

When Wells signed the Bilt deal, it counted on Millennials to make the same basic mistakes many Boomer credit card holders fall into that have allowed banks to rake in over $130 billion in 2023.

Little did they imagine Millennials would turn the tables with these strategies, turning the card into a runaway success, putting them in the driver’s seat for a change, boosting Bilt’s value, and making Wells Fargo the loser.

But to understand how all this is happening, let’s look at how the credit card industry works.

How banks cash in through credit cards

There are three basic ways banks make money from credit cards:

Interest

Fees

Interchange

Let’s take a look at how each works

Interest

Banks make the bulk of their money from credit cards by collecting interest.

Like a mob loan shark, if you still owe them money once your credit card bill goes past the due date, they start charging you for the loan.

And like a mob loan shark, credit card companies can raise interest rates at will, now charging an average 22.8% interest on $590 billion in balances for credit card companies in 2023, netting them over $25 billion in additional interest fees.

Once you owe credit card interest fees, together with compounding fees and penalties, you just keep getting deeper in the hole.

As we’ll see, this is one of the main income sources Wells was counting on to offset the Rewards Points they were paying for different transactions.

If you’ve ever missed paying your credit card on time, you know the next major way they make money: fees.

Fees

Using creativity and looking to squeeze everything they can from card users, fees are the range of additional charges banks tack on for any number of reasons:

Annual fees – More common with high-end rewards cards, banks charge you to keep your account open.

Late fees – As we touched on above, fees added when you pay your credit card bill late.

Overdraft fees – These are fees you get charged whenever you go over your credit limit.

Cash Advance fees – Among the highest fees banks charge, and start the minute you get cash against a credit card. (Hint: Never use a credit card to get a cash advance.)

Balance Transfer fees – When you move the amount you owe to another credit card.

But once they’ve flipped their customers upside down and shaken them for loose change, banks turn to another income source: the businesses you buy from.

Interchange

Bank’s next biggest credit card moneymaker is interchange fees.

Banks charge businesses swiping your card anywhere from 1-3% for every purchase you make to get paid back for the goods and services they’ve sold you.

So even if you have a credit card but pay it in full every month and never carry a balance from month to month, your bank still makes money off the stores you do business with every time you use it.

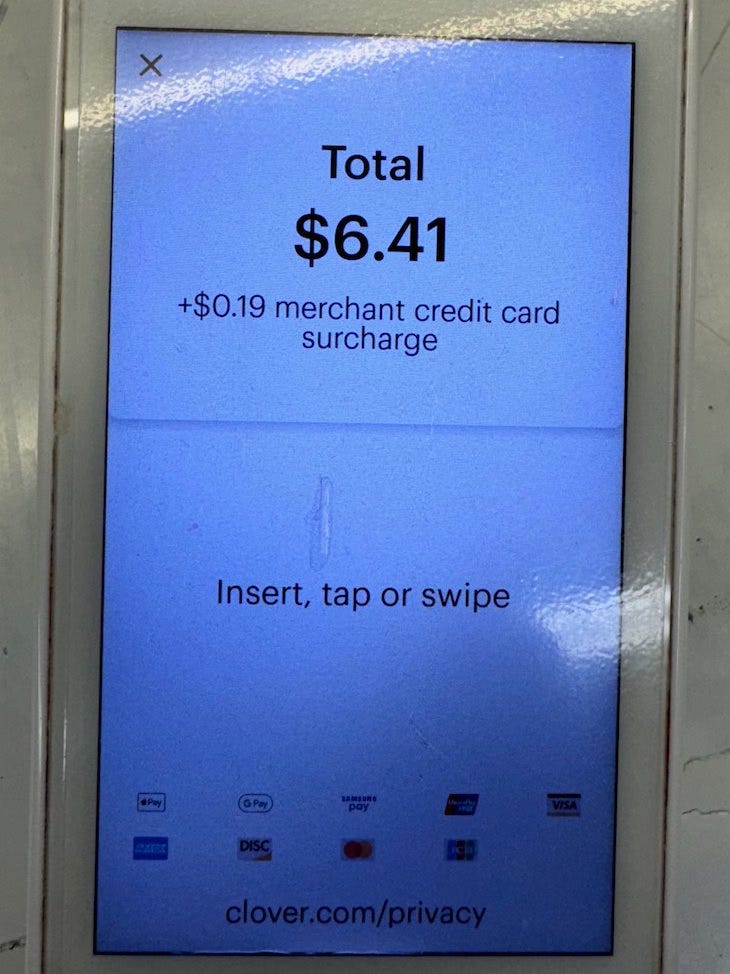

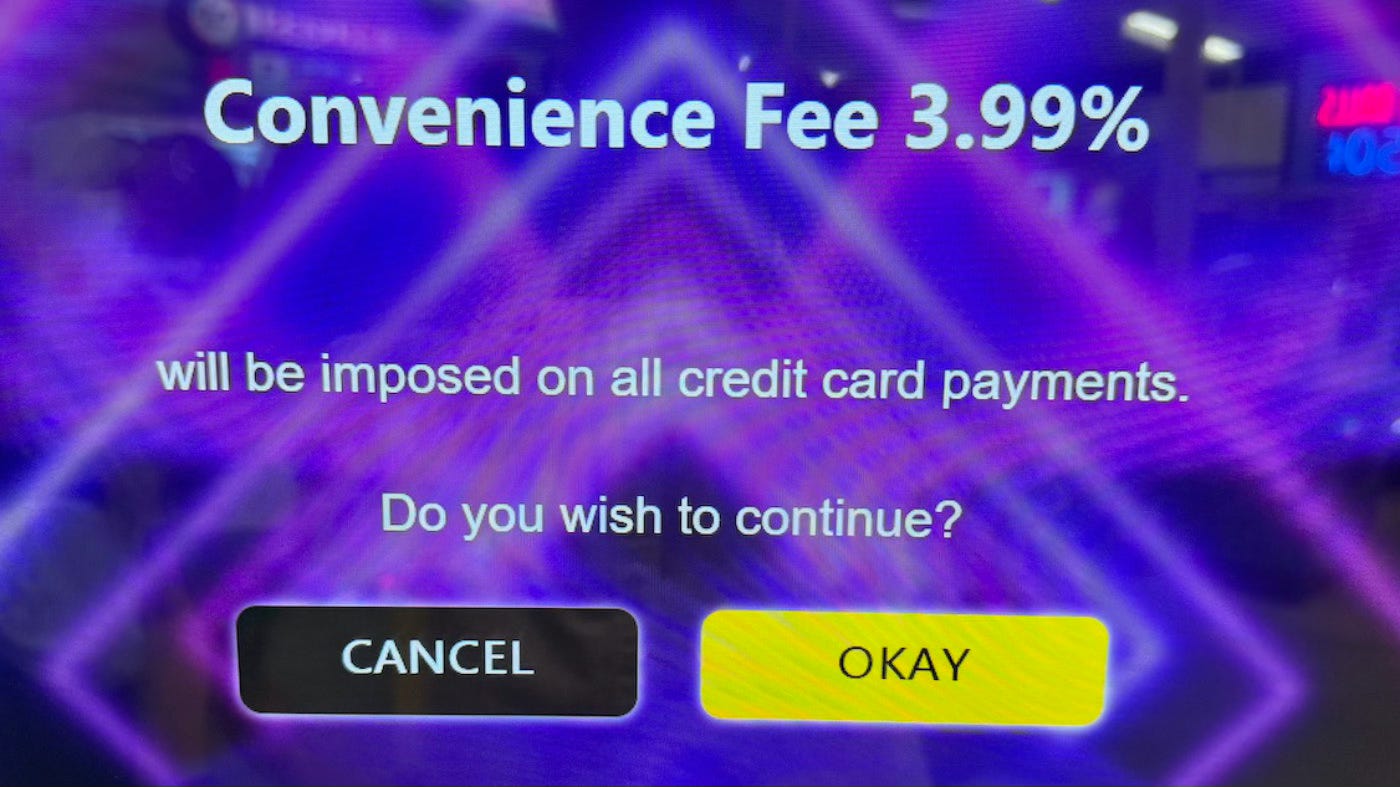

Some businesses fight back by passing these interchange fees onto the customer. So now both banks and the businesses are double-dipping the customer from both sides.

The examples below are from an ocean resort arcade and an ice cream shop:

So if you’ve ever seen or been charged those fees, now you know why.

All three together– Interest, Fees, and Interchange – provide banks with continuous income and fund their rewards points programs.

But sometimes, consumers need more of a reason to have a credit card.

This is where co-branded rewards cards come in.

The partner dynamics of co-branded rewards cards

Co-branded cards give a brand’s loyal customers an opportunity to carry a piece of that brand in their wallet.

Banks love co-branded partnerships because they get access to the brand’s customers. Because they are so lucrative, banks routinely pay their partners generous cash payouts for every customer signed.

Brands, in turn, can offer perks to their card users that cost them little yet seem highly valuable to their members.

Airlines were the first to use co-branded cards extensively. If you’ve ever had a flight attendant hard-sell a credit card, it’s because the airline gets $200 for every account opened.

Department stores, warehouse clubs, Amazon/Prime, and hotel chains are the other most common co-branded cards.

Co-branding not always a win/win

But co-branded credit card partnerships don’t always work out as planned.

With three parties involved—the two partners and the end-user customers—things can quickly get complicated and messy.

Long-time, loyal customers may be declined for a co-branded rewards card based on a low credit score.

When members sign up and run into issues, the issuing bank’s customer service may be slow or poor, creating a bad impression of both the brand and the bank.

Or, as in the case of the Wells Fargo–Bilt partnership, when one party wins at the expense of the other.

The Bilt-Wells deal

Some parts of the Bilt–Wells Fargo deal could be considered fairly standard for co-branded partnership card agreements.

But as we’ll see, there are a few factors that have led the rent rewards card to turn into a runaway success for Bilt and their customers, and such a colossal money-loser for Wells.

As we saw with airline frequent flyer cards, the $200 Wells Fargo pays for each new member Bilt signs is in line with industry co-branded partnerships. But on top of that, Wells also pays Bilt 0.80% of the interchange fees on each rent transaction, even though they’re not collecting those fees from landlords. With average monthly rent hovering around $1,500, that amounts to an average additional $12 for every transaction, against millions of monthly rent payments.

Wells also has to split the interchange fees with Belt for all the other non-rent purchases Bilt rewards customers make.

Add in some Millennial financial savvy, and we’ll see how these all become vital factors leading to the Bilt card’s success at Wells Fargo’s expense.

Bilt rewards

Before the Bilt card, renters were commonly hit with “convenience fees” by their landlords (1-3% of their rent payment) to recoup interchange fees banks were charging them.

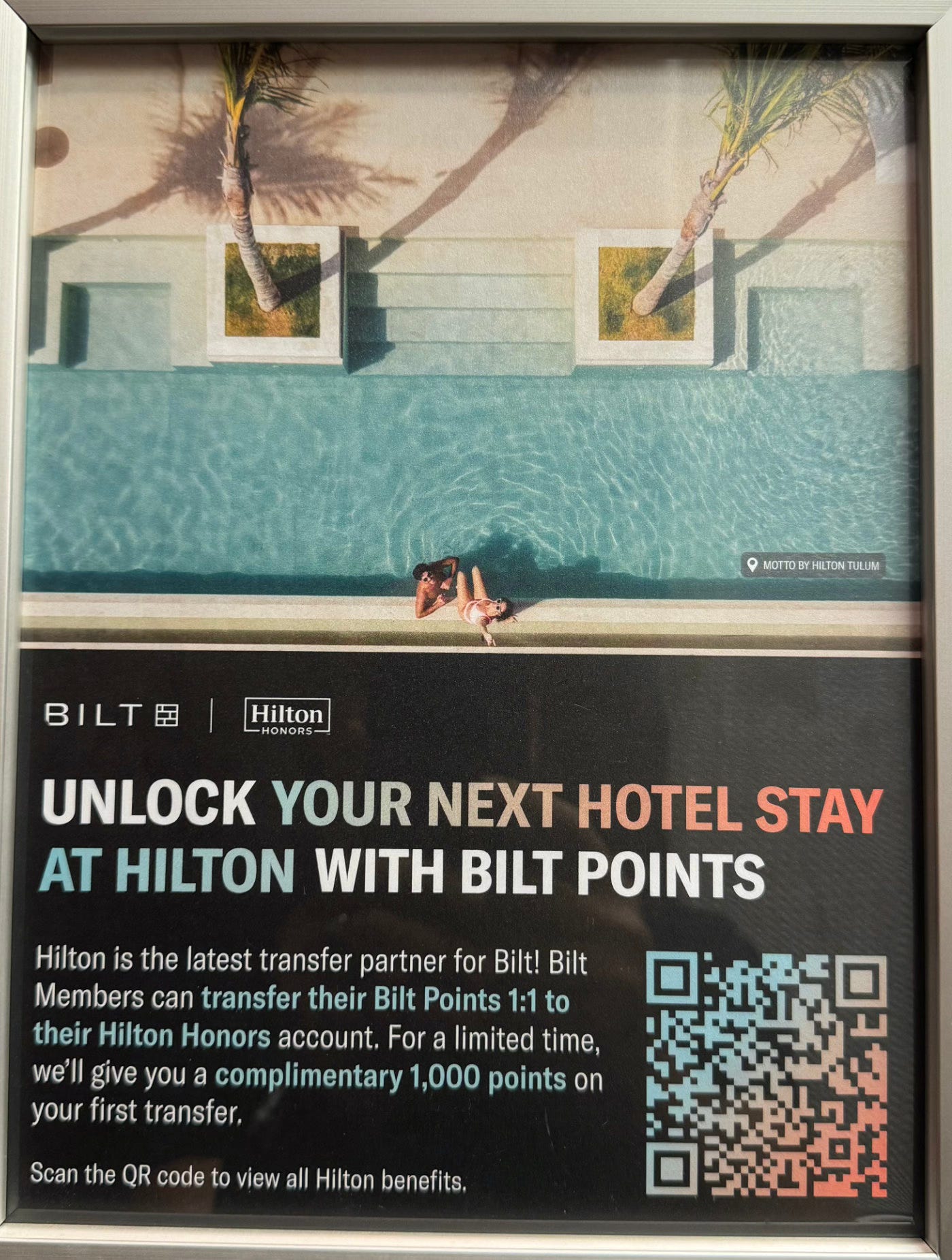

Bilt completely broke new ground by not only avoiding these fees for their renters, they sweetened the deal by rewarding members with points just for paying their rent with the card.

Besides rent rewards points, Bilt members earn 2X points for travel-related purchases and 3X for dining, which can quickly lead to some nice perks, like hotel nights.

Celebrating “Rent Day”

Bilt went one step further by revolutionizing “Rent Day,” or the first of each month.

Normally one of the most dreaded days for people who have to pay rent, Bilt instead turned it into a celebration by doubling points, giving members 4X for travel and an astounding 6X for dining.

And with over a million renters earning thousands of points monthly, Wells is on the hook to make good on those rewards..

What did Wells hope would happen by getting into the deal?

Wells’ strategic gambles

Wells Fargo made three strategic assumptions they believed would make it worth their while to partner with Bilt.

We’ll take a look at how each one of these assumptions matches up against the three main ways banks make money through credit cards.

Wells gambled their Millennial target customer would be naive and clueless, like someone who had just won the lottery, and would use the card to spend like it was going out of style.

But because Millennials haven’t turned out to be as financially clueless as hoped, the tables are turned, and savvy Milliennials are countering with the following strategies, now costing Wells upwards of $10 million/monthly:

Interest:

Wells’ Assumption: Wells believed the Millennials signing up for the card would carry balances of 50-75% of the dollars charged to the card, so they could rake in interest every month.

Reality: Only about 15-25% of the dollars charged to the card are carrying over, as Millennials are paying off their full card balance far before the due date, avoiding carrying a balance and the associated interest fees.

Fees:

Wells’ Assumption: As soon as cardholders missed a payment, they would be liable for substantial late fees that would snowball over time.

Reality: By paying off their cards ahead of time, they’re also wiping out this income source from late fees.

Interchange Fees:

Wells’ Assumption: Wells assumed that between the rewards on rent, travel, and dining, the Bilt co-branded card would become their new “card of choice,” racking up interchange fees with every swipe. They expected about 65% of their transactions to come from non-rent sources, and 35% from rent.

Reality: Because Millennials are savvy shoppers who tend to research and read the fine print, Wells Fargo’s hoped-for percentages have been flipped, with only 35% of charges coming from non-rent transactions.

Finally, Wells also hoped renters would eventually become buyers and take out home loans through their mortgage business.

So far, this hasn’t happened, and simultaneously, Wells has begun de-emphasizing its mortgage products.

Bilt prospers

With over a million users signed up for the card, 30-something CEO Ankur Jain’s rent rewards card startup’s value has skyrocketed by over 300%.

Bilt is now worth over 100%, from $1.5 to $3.1 billion, launching Jain into the ranks of first-time billionaires.

It’s not all bad for Wells Fargo

As of this writing, the co-branded Bilt card is less than two years old, so it’s too early to tell how things will pan out over the long term.

But Wells Fargo is clearly gaining valuable customers.

By paying $200 per user, their average new Bilt customer is 31 years old and has a 760 FICO score. Typically, acquiring these kinds of customers can cost up to 10 times more.

Still, losing $10 million a year, even for a bank as big as Wells Fargo, is straining the company, and they’re locked into the Bilt agreement through 2029.

As an interesting side note, Wells Fargo invested more than $20 million in Bilt back in 2021 at about a $300 million dollar valuation, so with Bilt’s 10X increase in value, they may yet see a return on that investment.

Summary and Takeaways

We now understand how banks make money with credit cards and the basics of how co-branded rewards card partnerships typically work.

We’ve also seen how those basics formed the foundations of the strategies Wells Fargo counted on in its co-branded deal with Bilt and how financially savvy Millennials are fighting back, exploiting the rewards card to their advantage at Wells Fargo’s expense.

You, too, can use these strategies to your benefit if you:

Pay off your balance by the due date

Use your card strategically, and only where you’ll get the maximum return and rewards

And remember, in strategy – it’s essential to watch your “What Would Have to be True” conditions like a hawk, and be ready to pivot when things don’t turn out as planned.