Why The World's Leading Strategist Says Data Is Killing Your Product's Future

Roger L. Martin, the strategic architect who reshaped iconic products like LEGO and Chevy Malibu, shares the missing keys to product innovation

I once worked with a company whose senior leadership followed their analytics dashboards with the anxious obsession of day traders stuck to their Bloomberg terminals.

Every tiny uptick brought giddy elation; every dip triggered panic and anxiety.

One day, I noticed some unusually panicked back and forth on chat. Their user numbers had apparently dipped slightly, and the team had launched into all-hands-on-deck mode like a submarine crew facing an oncoming destroyer, convinced some disaster was imminent. They wanted to analyze the problem immediately and have the engineering team rush out an emergency fix.

Two things struck me immediately - The first was the sheer intensity of their reaction. There could have been dozens of innocent explanations: seasonal patterns, a holiday weekend, or even normal statistical variation. The second was what they failed to do, which we’ll get to much later.

But because their dashboard had become their entire reality, even the tiniest dip had the ability to create an existential crisis.

Could Data Be Leading Us Astray?

This all-consuming reliance on analytics isn't unique to this company.

It's the default mindset in business today: without the data, it doesn’t exist. And whatever you can measure, you can control.

But what if this approach is fundamentally flawed? What if our obsession with data is actually causing us to miss meaningful opportunities, even preventing us from delivering innovative products?

Globally respected management thinker Roger L. Martin believes we're misapplying scientific methods in ways that kill innovation and prevent us from truly serving our customers in unique, breakthrough ways.

Martin points to examples of how some of the most groundbreaking products defied the data:

Apple’s iPhone catapulted them to become the world's most valuable company

Herman Miller's Aeron chair became history's best-selling office chair

TikTok overcame Facebook to become the premier social platform

Martin believes businesses are making a fundamental mistake widely understood 2,300 years ago: they’re misapplying scientific methods in the exact places Aristotle, the founder of science, warned us never to.

Aristotle’s Forgotten Ancient Warning

Through his consulting with global Fortune 500 CEOs, Martin witnessed one too many promising innovations die at overly data-driven organizations.

Martin’s deep understanding of Aristotle’s work helped him frame the critical distinction of the two realms:

The Realm of Analysis and Reason

Aristotle spoke of the realm where "things cannot be other than they are" as the area of science and physics.

Martin uses the example of holding a pen and letting go– Pens will always fall at the same rate because gravity is consistent everywhere. Data is useful in these predictable domains because we can use the scientific method to make a hypothesis, test it, and then analyze the resulting data to reproduce consistent results. Busines has many areas where the scientific method can be enormously helpful– analyzing tech system data, uptime, etc..

But there's a second realm where data analysis is not only less helpful—it can actively prevent innovation.

The Realm of Imagination and Creativity

Aristotle also spoke of the realm where "things can be other than they are."

This is the realm of creativity, design, and imagination where the future doesn’t have to look anything like the past. Martin believes businesses make their biggest mistake by forgetting Aristotle's explicit warning:

"In that part of the world [where things can be other than they are], do not use my scientific method."

Instead, in these creative, unpredictable realms, Martin believes we should follow Aristotle's prescription to:

"imagine a range of possibilities and choose the one for which the most compelling argument can be made."

Designers, strategists, musicians, authors, marketers, architects, copywriters, entrepreneurs, and, yes, even business people all do this by imagining entirely new possibilities and designing new futures that have yet to exist.

Misapplying the Scientific Method

Martin’s foundational insight is that businesses have ignored Aristotle’s forgotten caution and are misapplying scientific methods in areas they simply don’t belong.

This is why companies have more data than ever yet struggle with innovation and staying relevant in today’s rapidly shifting business environment.

Because business is one place where the world can be other than it is.

And there’s no better example than smartphones.

Who Needs a Phone in Their Pocket?

Smartphones were non-existent until the first real smartphone emerged with the Blackberry in 1999.

Now, there are almost 6 billion of them.

Also, think of all the massive businesses (Amazon, Facebook, Uber, AirBnB, etc.) built on top of them.

A rational analysis of the market conducted by McKinsey for AT&T in 1999 predicted smartphones would remain a niche market vertical of fewer than a million geek enthusiasts.

And that’s the problem with analysis– data only works if you’re working in an area where the past will continue to look like the future.

Unfortunately, business education is compounding the problem.

Here’s Why We’re Addicted to Data

As dean for 15 years, Martin used strategy to transform the Rotman School of Business from the "fourth best business school in Southern Ontario" to the top three globally.

But Martin sees a fundamental paradox in business education that runs directly counter to Aristotle’s warning. Every MBA program has a required statistics course, where you’re taught how to make inferences from a representative sample of data.

And within the same day, you could go into a strategy, marketing, finance, or business operations class, and you're taught to analyze whatever data to figure out what to do.

You even get graded for basing your decisions on data – any available data will do.

Trained to Misapply the Scientific Method

Freshly-minted business school graduates are told they’re now part of the “elite” and led to believe that because of their analytical training, they’re able to make better business decisions than anyone else.

But Martin believes business education leaves new MBAs with two areas of “blindness”:

They become wildly overconfident about the “correctness” of their decisions based on very little past data

They tend to become more conservative, shying away from areas of potential innovation

This leads these managers to miss potential opportunities and marginalize imagination and creativity.

This is why Roger Martin believes that business involves creative possibilities as much as scientific ones.

For me, what we lose in over-emphasizing data and scientific methods is empathy for users. They get reduced either to numbers on a dashboard or vehicles from which to extract numbers of revenue projections.

Fortunately, “professional” managers were not part of the decision-making process for the breakthrough products Martin likes to use to prove his point.

The Exceptions That Prove Martin’s Point

iPhone

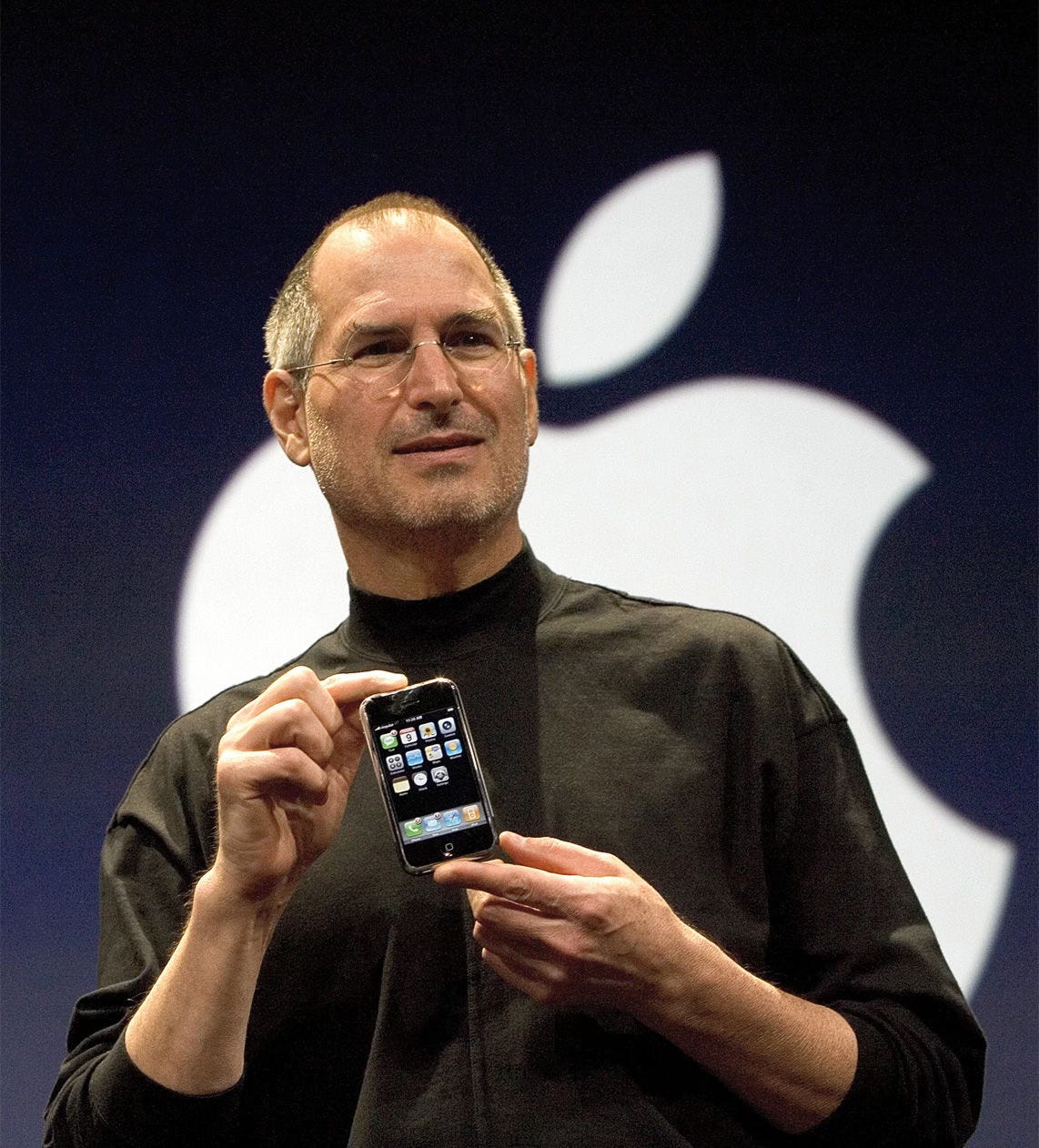

Martin sees Steve Jobs' lack of reliance on traditional market research as he and his team developed the iPhone at Apple as the pre-eminent example of “inventing the future.”

For Jobs, design wasn’t just how something looked but how it worked and felt in one's hand. While critics argued Apple’s meticulous attention to design and detail was too expensive, Jobs built a unique culture of empathy for the right target users, profoundly understanding their unmet needs and desires for devices that transcended basic utilitarian functionality. The iPhone embodied unusual empathy by allowing every application to benefit from a different keyboard, something only the iPhone’s touchscreen could offer.

Apple's culture of empathy shines through in how they continue to embody the phone’s integrated emotional and experiential aspects over “must-have” features that may have tested well in market research. This has made the iPhone the ultimate “halo” device, as satisfied iPhone owners enhance their experience by investing in more Apple ecosystem products, such as AirPods, the Apple Watch, etc.

And this was the key that made the iPhone the catalyst that took Apple from the brink of failure to the world’s most valuable company.

Nothing could be a clearer example of Roger Martin’s channeling Aristotle’s realm of “imagination,” where things can indeed “be other than they are.”

The Aeron Chair

The Aeron chair failed miserably in market testing, with some customers even asking, "Why did you make me sit on an unfinished chair?"

But the Herman Miller design team felt good about their chair. So with no data to support their decision, they went ahead and manufactured and launched it.

What they did have was empathy for their target users. And they felt confident those users would find the chair fit their needs because it solved several serious problems desk chairs suffered from at the time.

Without data, but with imagination and empathy, the Aeron rapidly went on to become a status symbol of startup success and the "best-selling and most profitable chair in history"

TikTok

Martin believes TikTok defied the network economics that should have made it easy for Facebook to destroy it in the same way it was able to destroy potential upstart Snap.

Network economics helps us understand how platforms gain in value as more users join, leading to unbeatable, “winner-take-all” situations. Over the years, Facebook successfully used massive piles of investor cash to build and aggressively protect its network against scores of potentially competing apps and networks.

TikTok overcame Facebook's overwhelming user base and optimized feature set advantages by removing users' need to scroll through their feeds. Instead, TikTok prioritized empathy by dropping users in the middle of content hyper-targeted to their interests, grounded in community, and accompanied by delightful content creation tools so anyone can create content and contribute to further building out their community.

Martin believes TikTok's success lay in creating a platform that allowed people to join the kinds of worlds they wanted to be part of and allow others to join and contribute to them easily.

From Analyzing Data to Engaging with Community

Martin sees the next generation of business as moving from optimizing products for individuals to taking a page from TikTok’s book and creating entire communities and worlds people want to be a part of.

Coming back to the company I referred to at the beginning of this piece, the second thing that struck me about their dashboard dip panic was how they failed to reach out to their community.

Because sometimes the most important signals to pay attention to aren't on any dashboard.

There’s no data from the past we can analyze that will help us better understand and develop empathy for user needs.

Only through speaking with customers and understanding what they’re going through can we use imagination and creativity to innovate and devise unique ways to address their unmet needs, hopes, and desires.

The Road to Becoming the Next Outlier

Martin believes we need more leaders who can look beyond the numbers.

The company I worked with could have used more of a strategic- and user-centricity focus, and far less of an emphasis on data to develop greater empathy for their users.

And there’s no more important design-driven statement of empathy than

“Design with, not for.”

Drawing from another of Roger L. Martin’s insights, the company could integrate simple community-building tools into their product, allowing users to share challenges and successes along their own journeys.

My final challenge for your company's next breakthrough is to look beyond analysis and data and instead use more creativity, imagination, and empathy for your users.

What smaller opportunities or more significant breakthroughs might your product be missing because of an over-reliance on quantitative measures and dashboard addiction?

And what breakthroughs might become possible if you're willing to imagine a different future, take your time, and have the courage to see it through?

Great article. There’s got to be a balance - without reliable data, you're flying blind. But relying on data alone isn’t always enough either.

Sometimes you need to trust your gut, just like Steve Jobs did. The iPhone XS launch wasn’t perfect, and that’s where data analytics helped course correct.

Both matter. It’s knowing when to lean on which.

Dear Mike, I read the note about your article and your article in Spanish, I like it:

https://substack.com/@cienciasocial/note/c-111083653